An often overlooked feature of moral life is that there is an ethical obligation to at least *try* to think critically and objectively. One useful entry point into understanding why this is the case, is the virtue of “intellectual empathy”. This idea has very little to do with emotion or sentiment. Intellectual empathy is simply about putting yourself “in the mind” of someone else, and trying to imagine how a person might reasonably come to have the position they have. The key word here is reasonably. Essentially, in exercising intellectual empathy, you are trying to construct a plausible case or a credible intellectual story that makes sense of the kinds of things that the person you are in conversation with (or whose claims you are evaluating) is saying. Part of that story might have something to do with motivation or emotion. But mostly, it is a question of trying to establish a reasons-based account of why the person might plausibly have arrived at their position.

Now this might at first seem like a strange thing to suggest if in fact you are already engaged in a conversation with someone. Couldn’t you just ask the person to explain why they believe what they believe, and base how you respond on that? Certainly that is part of what being a good interlocutor is about. But the point here is that, even the kinds of questions that you ask someone are influenced by certain (sometimes unconscious) assumptions you make about how the person reached the conclusions they reached. Also, how you respond to what they say may likewise be coloured by your assumptions about why, in general, the person thinks the way they do. Let’s look at an example to illustrate.

Suppose that I am a political conservative, and one day I get into a conversation with a socialist. The first question I ask is, “why do you hate liberty?”. The socialist seems put out by this question, and responds by saying that they do not in fact hate liberty, that they simply believe that true liberty can only be achieved if major industry is brought under the democratic control of workers. I respond by saying “Ah I see, so you want politicians to run our lives! What a joke!”. The socialist starts to become agitated, and responds angrily that I have misrepresented what he believes. The conversation rapidly devolves into personal insults and resentment.

You can create an equivalent story from the other side – a socialist meeting a conservative and asking “why do you hate poor people?”, and so on. The point here isn’t to claim that conservatives or socialists habitually do this kind of thing (I have seen it on both sides, as I’m sure most of us have). The point is that the line of questioning in the example above points to a set of background assumptions about the socialist that manifest a lack of intellectual empathy. I, as the political conservative in the example, apparently think that one of the main motivations for socialists is hatred of liberty; and that they have constructed their political vision with a view to destroying it. I also seem to assume that they have a naïve, blind faith in politicians. Now without wanting to get into the weeds about what socialism is or is not, the point here is that I clearly have created a highly implausible motivational and rational backdrop for this person’s belief in socialism. How reasonable is it really to think that a person would be genuinely motivated by (or happy to accept) a hatred of liberty, and a blind faith in politicians? Is that really a credible thing to think about someone? Is that a plausible intellectual path that would bring a person to that perspective?

The obvious answer here is “no”. Almost no one would ever think that way. This isn’t to say that there might not be some people out there who, say, have too much faith in politicians; or who don’t have enough respect or love of liberty. But almost nobody in the real world is going to literally hate liberty, or trust all politicians blindly. And there’s no credible intellectual story a person can tell about a socialist, say, such that those are among the main motivations and reasons for holding their position.

Instead, I as a political conservative should think about motivations that I could imagine having that might lead me to believe in socialism. I should construct a “background story” that imputes psychologically realistic motivations and reasons to the person I am engaging with – such that I could imagine how and why I could come to such a point of view as well. What reasonable values might bring a person to socialism? What kinds of commonplace experiences might move a person in that direction? Asking these kinds of provisional questions in your own mind, whatever the topic or area of debate, is good intellectual practice.

Why? Because it makes it less likely that you will alienate, insult or appear to belittle other participants in a discussion or debate. If you impute obviously ridiculous or extreme motivations and values to others, they are going to (not unreasonably) conclude that you perceive them as intellectually naive, or stupid, or malevolent – or all three! However, if you manifest intellectual empathy (and this should come across in the kinds of questions you ask), you are more likely to foster a productive, sustainable and respectful discussion. Again, there may be rare cases where you will encounter someone with extreme views. But if that is the case, soon enough they will make it apparent to you as you probe and question them. But the probing and questioning should proceed on the basis of plausible, provisional assumptions about their motivations and reasoning.

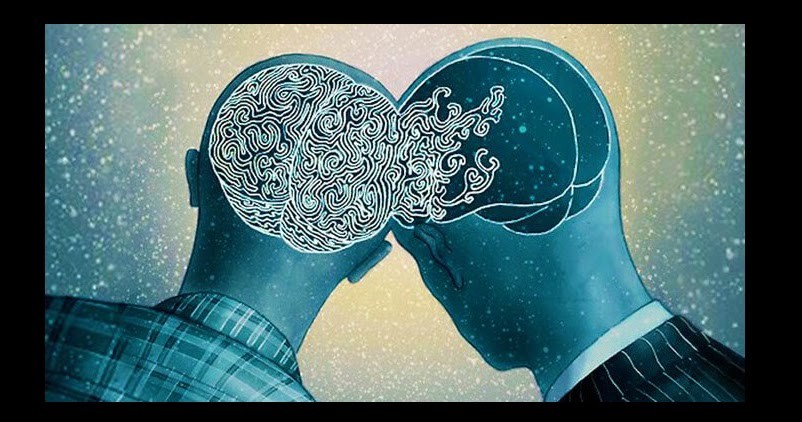

Intellectual empathy is perhaps the “master” virtue of being a good interlocutor, and from it one can derive all of the principles and best practices you will find in the next four lessons. Striving to manifest intellectual empathy can be a challenge, because as we’ll see, the temptation to “strawman” other people’s views can be very powerful. It is about putting yourself in the “cognitive shoes” (rather than the emotional shoes) of another person. And it can require suspending many of your pre-existing assumptions about certain groups or certain belief systems. But the effort is almost certainly going to pay off in the form of improving the quality and durability of discussions and debates.